But what to do about supplies? It was agreed that a “not guilty” decision was no longer enough. Hepler’s letter and the ten days of research at UCLA conclusively showed that marijuana was essential to Bob’s sight. How to get legal marijuana? Judicial exemption to cultivate our own supplies? Should we petition the Supreme Court? Perhaps the Congress could grant Bob a special exemption?

In the midst of all this animated discussion I suggested, “why not ask the government for their marijuana?”

Why not ask the government for their marijuana?

According to Bob’s journal this suggestion stopped everyone in mid-conversation. Both the lawyer and Bob tried to reject the idea. But the harder they tried to reject the possibility on legal ground the more intriguing it became.

So, our case took on a Two-pronged attack at that point – the criminal defense and a petition to acquire federal supplies of marijuana. Crafting the petition for legal access proved to be more difficult than first supposed. Marijuana was tightly controlled and there did not seem to be an option for individual access to the drug. But our attorney charged ahead, filing a petition with the Drug Enforcement Administration and the DHEW in late May 1976, citing both the UCLA and a later study at John Hopkins University which demonstrated, once again, that no combination of existing drugs could control Bob’s glaucoma. The lawyer made it quite clear that further legal action could be pursued based on the strong evidence in-hand.

The Two-Pronged Attack:

- Legal defense at criminal trial based on Common Law tenet of “necessity” — those cases in which one must break the law because to obey the law would bring greater harm

Within the bowels of the federal government there was some low grumbling as things began to move. Ours wasn’t the first petition to arrive on their desk. The NORML petition to reschedule marijuana was already four years old at this point and the feds were stonewalling that request with little effort. But Bob’s request wasn’t a broad-sweeping petition from a bunch of pot-smoking hippies. This was a real human being, facing one of the scariest prospects that life can deal you – blindness. And the government’s own researcher was backing this guy’s claim. The feds quickly realized that some resolution must be crafted. Failure to do so left the entire system open to attack.

In July the criminal trial opened in Washington, D.C. The lawyers had a novel defense: not guilty by reason of medical need. There was nothing like it in the annals of modern law. So the lawyers reached into the past and based the defense on a tenet of Common Law – necessity, which dictates that an individual is innocent of breaking the law if circumstances compel him to do so in order to maintain his life or well-being.

Necessity:

Necessity is the conscious, rational act of one who is not guided by his own free will. It arises from a determination by the individual that any reasonable man in his situation would find the personal consequences of violating the law less severe than the consequences of compliance.

Because of the uniqueness of the defense, we opted for a non-jury trial and the gods favored us with Judge James Washington, former dean of Howard University Law School, a scholar who listened intently to the prosecution and defense. He took the case under advisement and would then take four months to decide the case.

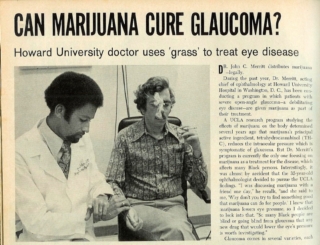

As Judge Washington worked on the legal decision the feds were crafting an interesting solution to the lawyers’ petition for legal access to federal supplies of marijuana. Schedule I dictated that marijuana was available for “research purposes only.” So what the feds needed was a research program in which to plop Bob Randall. It was suggested that he move to California but both Bob and Dr. Hepler rejected this idea. Once again the fates intervened. In August an enterprising ophthalmologist in Washington, D.C. contacted the National Eye Institute about his interest in doing research on the effect of marijuana on glaucoma. The NEI official contacted NIDA, which was working with Bob, and NIDA put its full-weight behind expediting the approval of the program.

Bob clicked easily with the doctor, Dr. John C. Merritt and became the first patient in the Howard University-based program. There would be weeks of ironing out the details of Bob’s actual access to the drug. Silly, stupid requests and/or demands were made. Week after week went by. Each one brought some new crisis or demand from some fed agency. Each demand was rejected as out-of-hand and Bob’s scientific evidence was so strong that the feds knew they were between a rock and a hard place.

- Report to Howard University each time Bob needed to smoke (proven by UCLA to be ten times a day).

- Secure take-home supplies in a 250 lb safe, bolted to the floor from the inside.

- Alternatively, a 750 lb free-standing safe could be used.

- Do NOT speak with anyone about his use of marijuana.

Government Demands:

Everything congealed in November 1976. Merritt received his supplies from the federal government in early November and quietly started supplying Bob with marijuana.

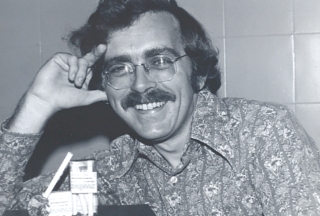

Dr. John C. Merritt and his patient, Bob Randall

Twelve days after Bob received his first supplies from Merritt Judge Washington issued his decision in the case, finding Bob not guilty by reason of medical necessity.

The closeness of these two events made for wonderful press coverage. The press LOVED the story. And Bob LOVED the press. In those first six months following his legal access, there were calls from every imaginable press outlet — from CBS Nightly News to suburban papers in America’s heartland. Radio talk, TV shows from the Good Morning America to the game show “To Tell the Truth.” It was an exciting time. Bob would often be recognized on the street and always the comment was the same, “You’re that guy! The guy who smokes Uncle Sam’s pot.”

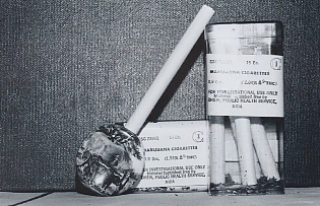

Bob Randall w/Legal Medical Cannabis

In November 1976, everything seemed to be resolved. But in the coming weeks and months problems arose. The federal solution was a house of cards – hastily thrown together to address an urgent legal request. And the feds were less than happy with the outcome. Bob seemed to be everywhere talking about the therapeutic benefits of marijuana and other patients were now calling federal agencies with their requests for access. And patients called us too.

“As America’s only legal pot smoker I felt like the only man to reach the lifeboat. I was the sole exception to a catholic and absolute prohibition. It was a position of great peril and possibility.”

Marijuana Rx, page 134

In the Spring of 1977, Bob organized 13 of them and filed a petition with the Dept. of Justice to re-schedule marijuana. Among them was a 62-year old retired school teacher in Wichita, Kansas, Ara Cron, who had glaucoma and proved adept at making her own press. This only antagonized the feds even more.

In an effort to stem the rising interest and demand, the federal government began a series of supply disruptions at the Howard University program. These were directly connected to Bob’s outspokenness and served to drive a wedge between Bob and Dr. Merritt. Merritt, a young and ambitious ophthalmologist, was not interested in resolving the political battle over marijuana. He simply wanted to advance his career and making waves was not the way to do that.

“Having failed at numerous other attempts to ‘rein me in’ the government finally found the weak link–Merritt. The bureaucrats at the DEA and FDA and NEI were willing to pay Merritt a very hefty price to disrupt my legal access–$95,000 per year for 3 years plus a professorship at UNC.”

Marijuana Rx, page 148

Less than a year after Bob first received his marijuana the “resolution” crumpled before our eyes. Dr. Merritt was offered a lucrative position at the UNC in Raleigh. Bob was always suspicious that this “offer” was crafted by federal officials in order to disrupt Bob’s legal access and silence him. There seemed to be little concern that Merritt’s departure would throw Bob into a crisis of medical care.

Merritt left D.C. in early 1978 and things got very grim. Ironically the issue was heating up across the country. In California a judge authorized a cancer patient to receive supplies of marijuana from the local sheriff and immunized his family from arrest and in New Mexico debate was underway on what would become the nation’s first state law recognizing marijuana’s therapeutic utility. But Bob’s prospects were dismal. The press seemed to care less that the nation’s first legal marijuana smoker may now go blind. Federal officials had slammed the door on him. NORML did not have the funds to muster the massive Constitutional case that would be legally required at this point in time.

“I learned that getting legal marijuana was news. Losing it was being just like everyone else. Being like everyone else ain’t news.”

Marijuana Rx, page 163

We seriously discussed moving to North Carolina.

But Bob managed to pique the interest of UPI reporter Dave Anderson and on January 25 a story appeared on page three of The Washington Star. It caught the attention of a young lawyer at Washington’s third largest law firm. And when the firm of Steptoe & Johnson agreed to represent Bob on a pro bono basis in early February 1978 we suddenly found ourselves on an equal footing with the feds.